EXCINERE® IS A REFINED COLLECTION OF VOLCANIC ASH-GLAZED TILES DEVELOPED IN COLLABORATION WITH FORMAFANTASMA.

The result of more than three years of research and experimentation, ExCinere® is suitable for both interior and exterior surfaces, from kitchen counters and bathroom floors to architectural facade cladding.

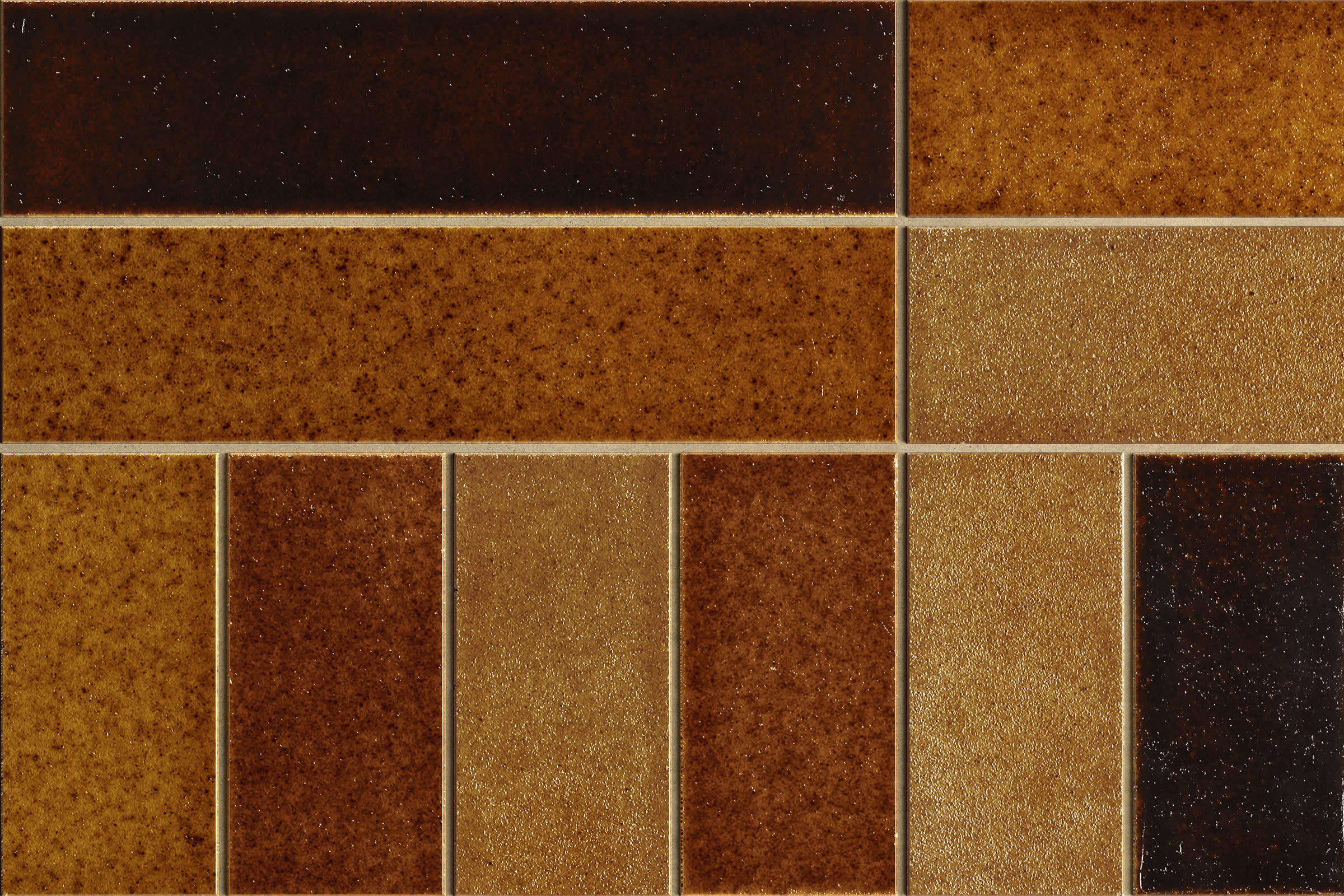

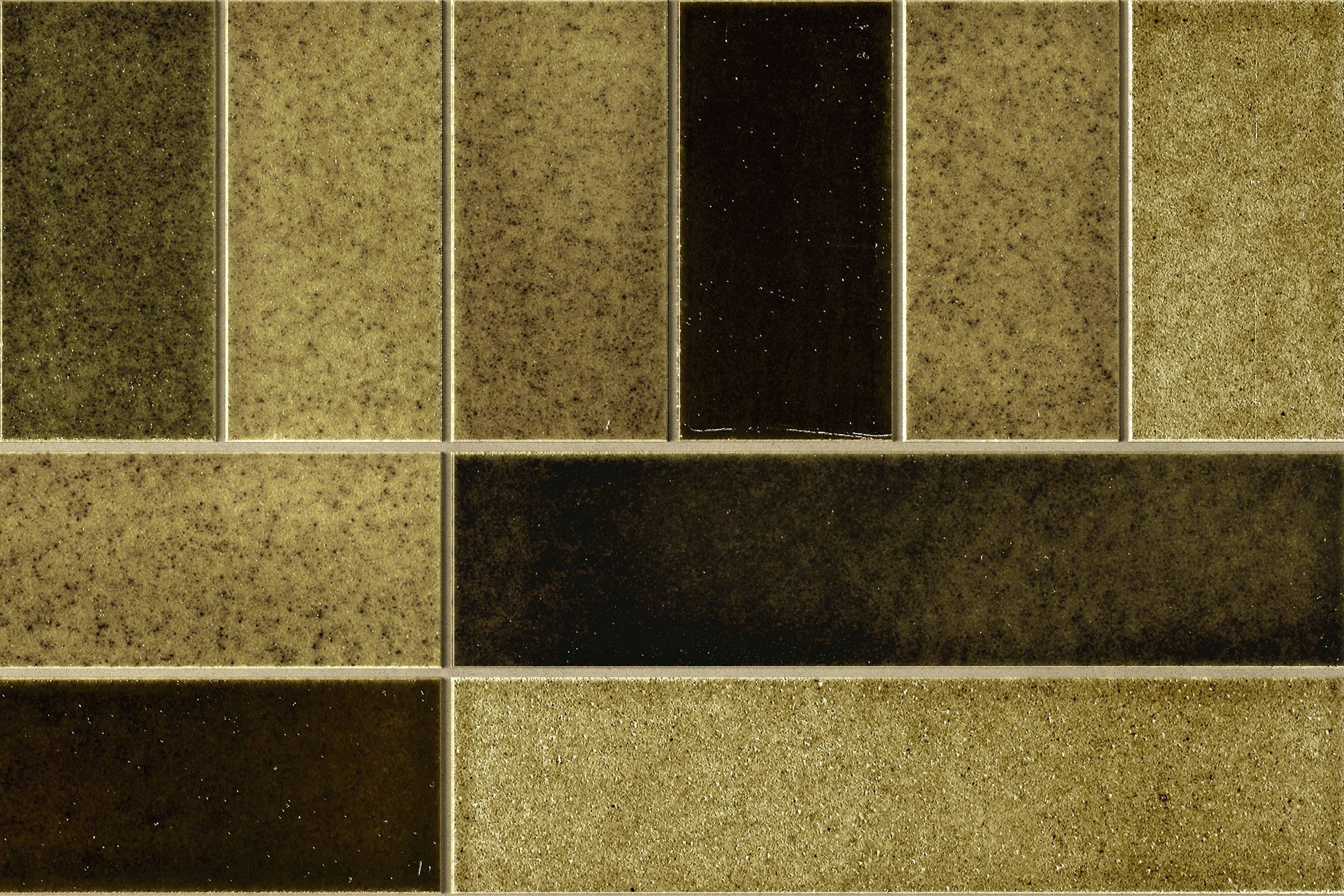

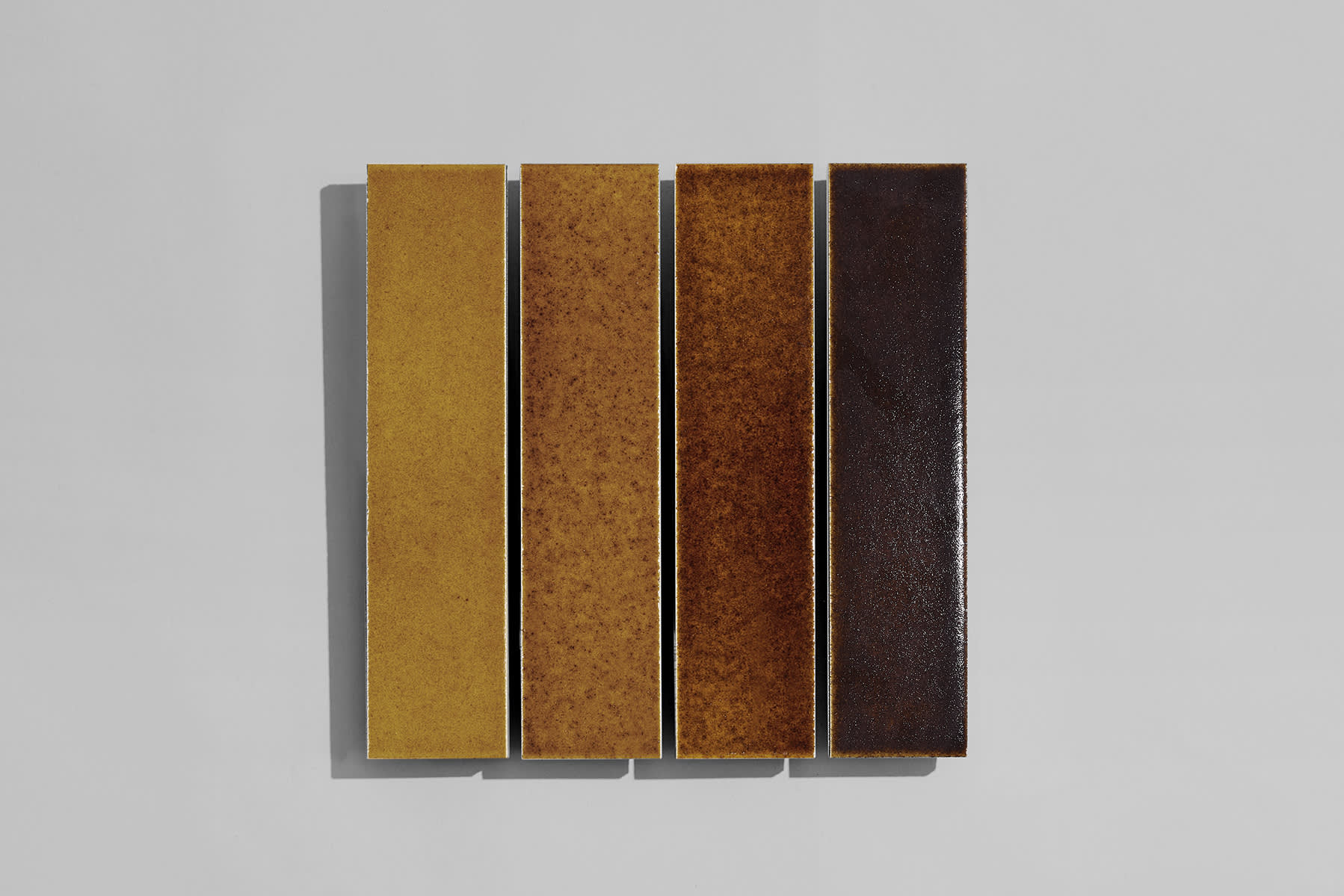

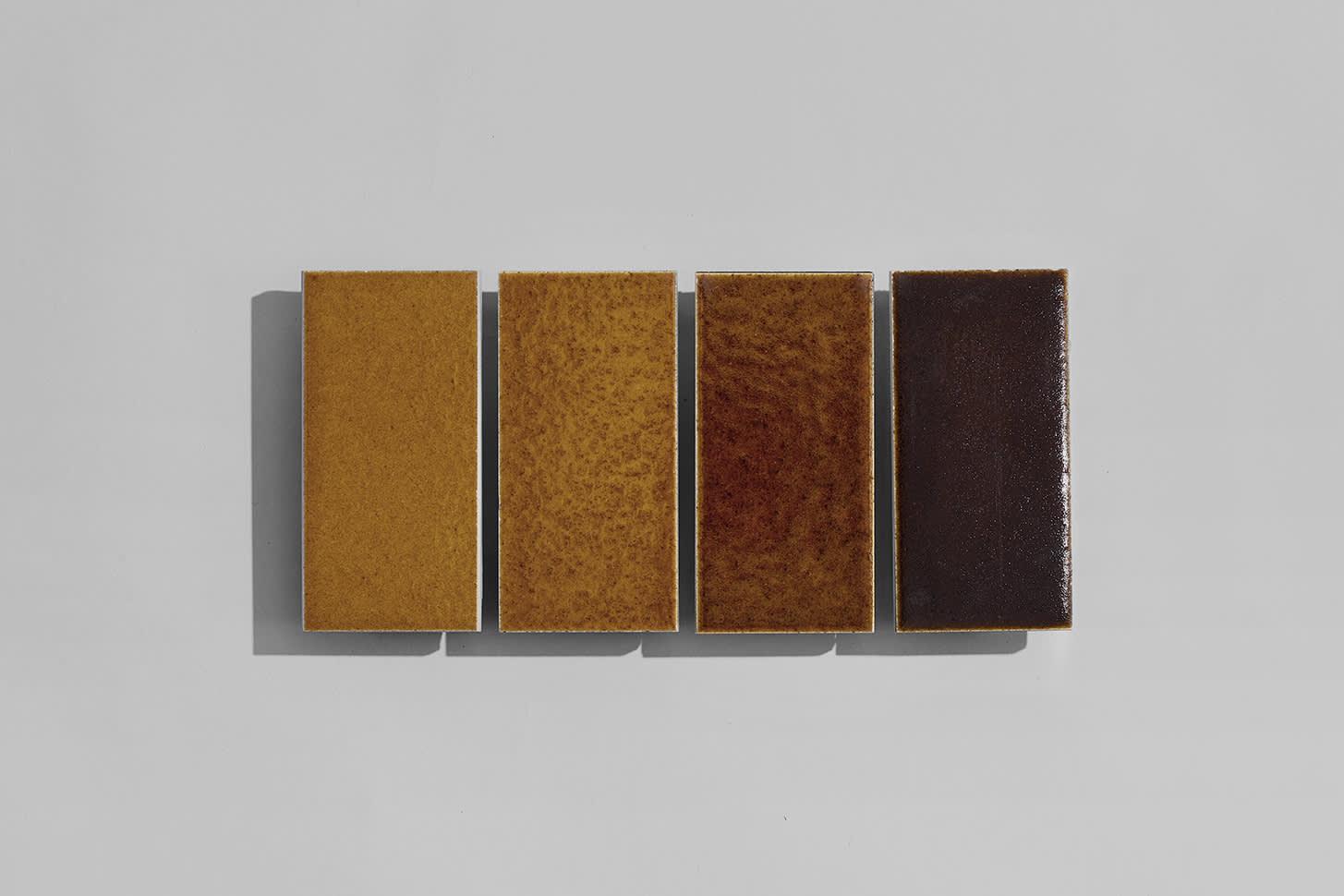

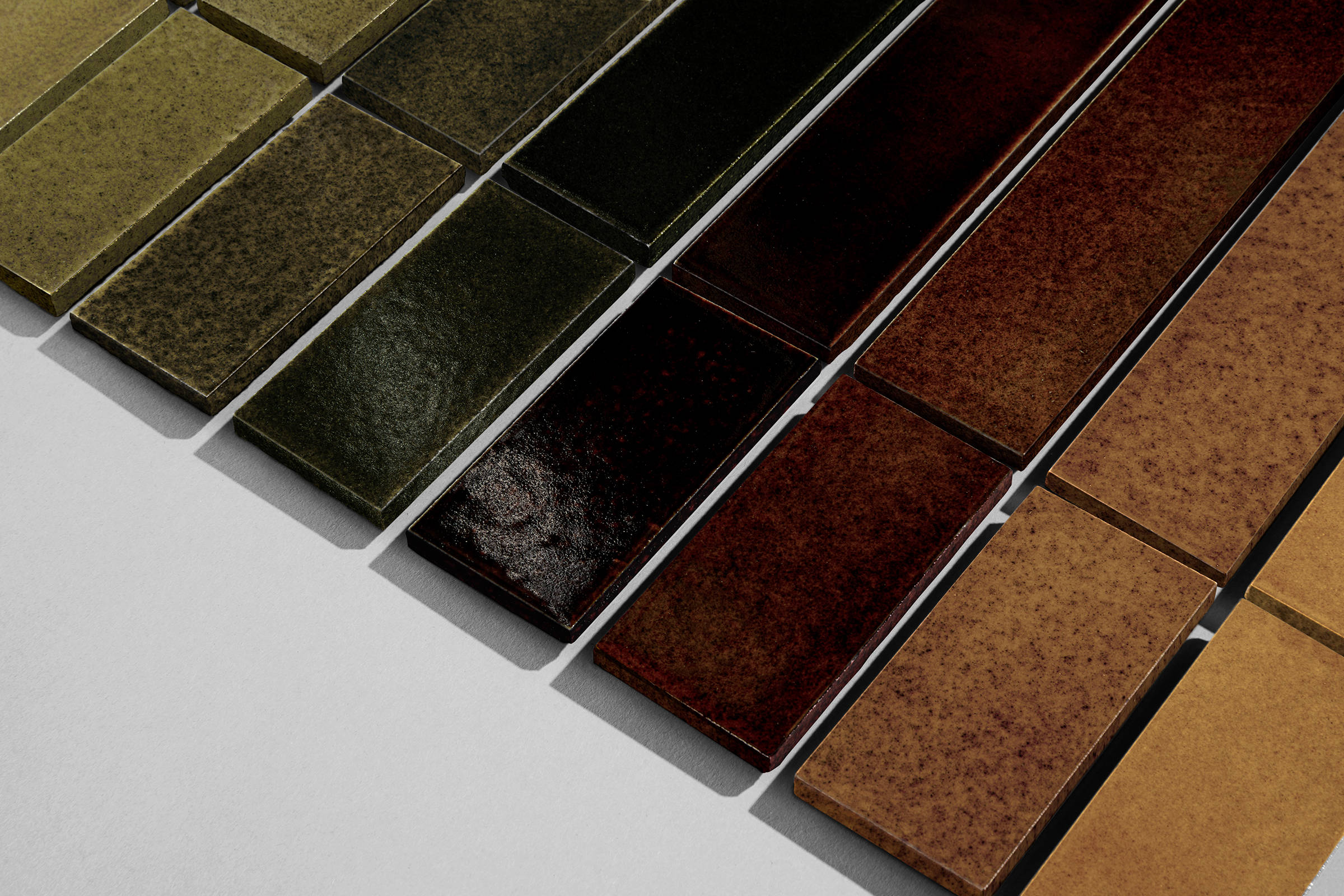

The collection is available in two standard sizes and two volcanic ash-glaze ranges, our classic Terra range with four earth tones and the new Verdigris range in four earth-greens. The different glaze colours and textures are derived from mixing and firing varying quantities, particle sizes and densities of volcanic matter are evocative of the dynamic landscape from which they come.

The name ExCinere® is a play on the Latin ex cinere, which means ‘from ash’.

FORMATS + FINISHES

ExCinere® is available in two sizes and eight volcanic ash glazes, allowing for infinite compositions across both interior and exterior architectural surfaces.

Special finishes and corner formats are also available, including high slip-resistance options for wet flooring areas, as well as mitred or glazed profiles for corners and edges.

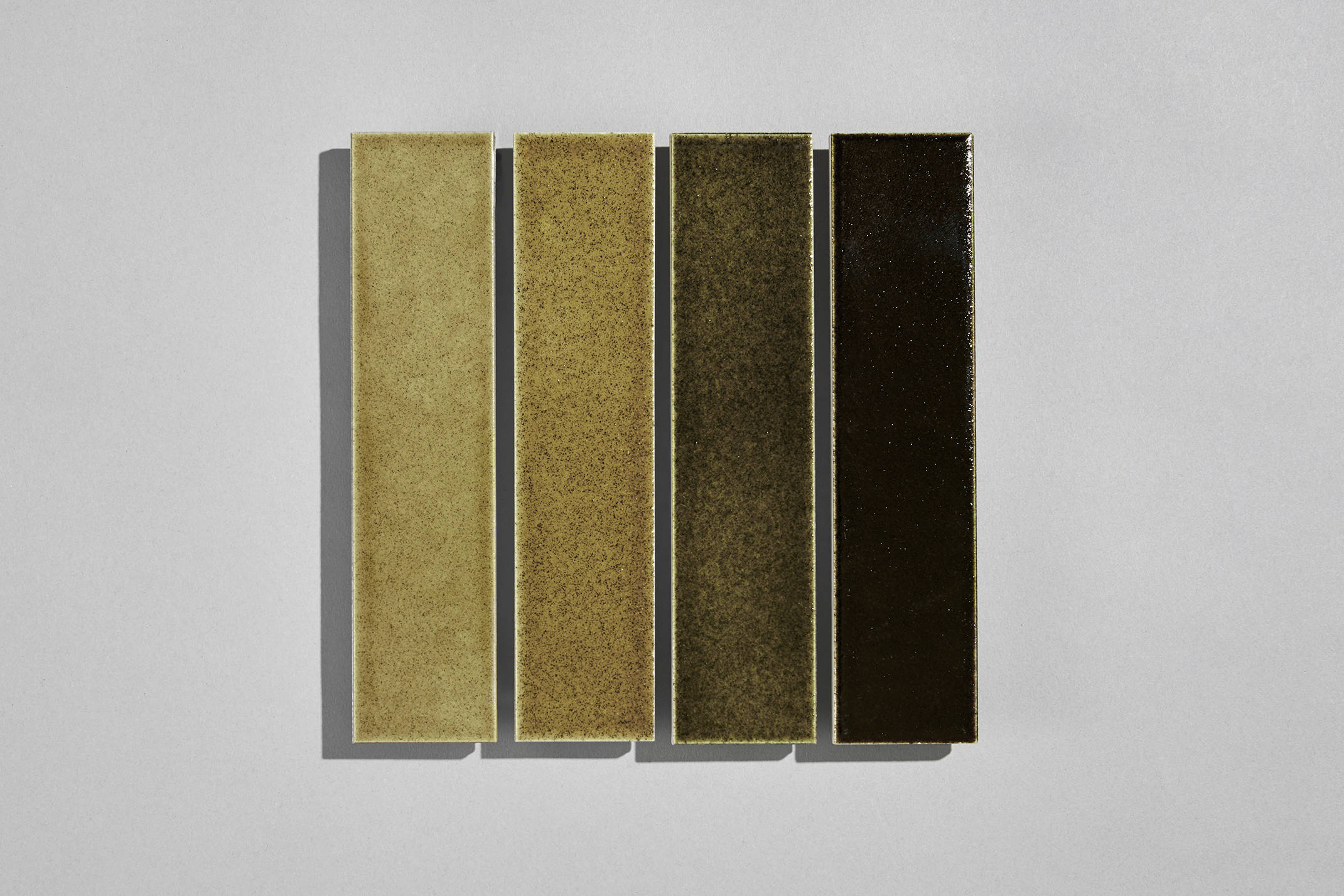

EXCINERE TERRA IN THE 198 ✕ 48MM FORMAT, GLAZES A, B, C, D.

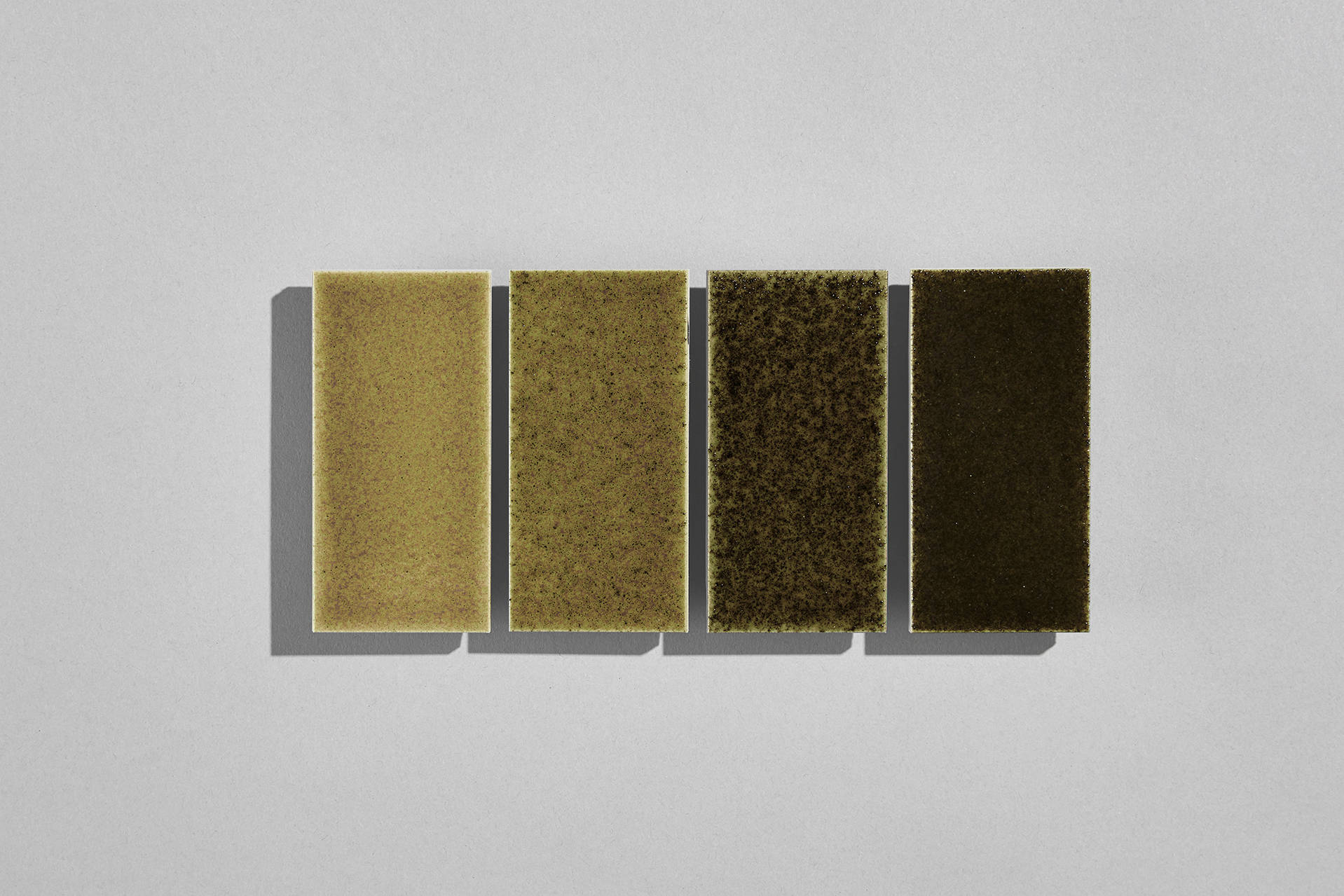

EXCINERE TERRA IN THE 98 ✕ 48MM FORMAT, GLAZES A, B, C, D.

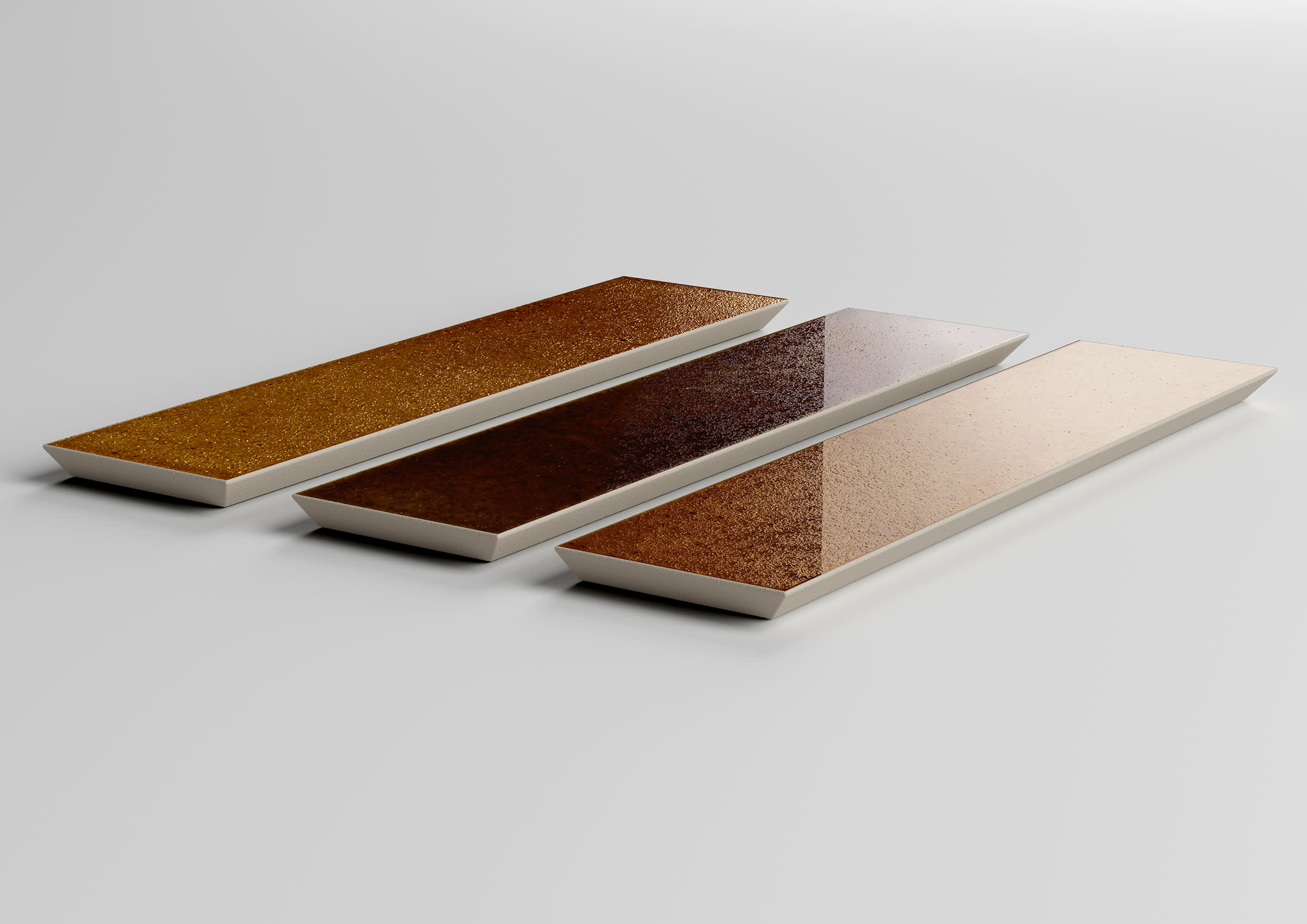

EXCINERE VERDIGRIS IN THE 198 ✕ 48MM FORMAT, GLAZES E, F, G, H.

EXCINERE VERDIGRIS IN THE 98 ✕ 48MM FORMAT, GLAZES E, F, G, H.

EXCINERE JOLLY TILE (45º MITRE CUT ON TWO ADJACENT EDGES)

EXCINERE JOLLY TILE (45º MITRE CUT ON TWO ADJACENT EDGES)

EXCINERE GLAZED EDGE TILE

| TILE | SIZE | THICKNESS | GLAZES |

|---|---|---|---|

| VOLCANIC ASH GLAZED PORCELAIN | 98 ✕ 48mm (S) | 8mm | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H |

| VOLCANIC ASH GLAZED PORCELAIN | 198 ✕ 48mm (L) | 8mm | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H |

| JOLLY | L, S | 8mm | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H |

| GLAZED EDGE | L, S | 8mm | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H |

HOW TO BUY

Tiles are sold in 0.25 m2 boxes of a single size. Boxes of 98 ✕ 48mm tiles contain 50 units while boxes of 198 ✕ 48mm tiles contain 25 units. Jolly and glazed edges tiles are sold by the unit.

All glazes are hand applied, made using organic matter and are batch produced. Therefore each glaze will contain subtle variations in colour and texture within each production and from batch to batch.

We ship worldwide from Italy. Lead times are generally 2-8 weeks for fulfillment. Transport times depend on location and method of shipping. When you have specified material quantity and shipping destination, we will source multiple quotes (air and sea available) and pass along the option that best suits your needs.

| BOXES | GLAZES | SIZES | UNITS PER BOX | M2 PER BOX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MONO | SINGLE GLAZE | SHORT/LONG | 50/25 | 0.25 |

| POLY, TERRA | MIX OF A,B,C,D | SHORT/LONG | 50/25 | 0.25 |

| POLY, VERDIGRIS | MIX OF E,F,G,H | SHORT/LONG | 50/25 | 0.25 |

CASE STUDIES

STORY

The use of volcanic matter in architecture has a long and rich history. From the Bronze age Jardines of Pantelleria; strong protective walls built around delicate fruit trees in raw volcanic rock, to Roman concrete; a material including pulverised lava rock added for durability, to César Manrique’s evocative Lanzarote architecture of the 1960’s which so seamlessly and sympathetically integrates into its surrounding volcanic landscape. ExCinere is a new take on the tradition of volcanic lava as building material and a manifest of the enduring attraction between humans and the impossible force of nature.

Simone Farresin and Andrea Trimarchi explore the Etna landscape.

THE PANTHEON IS AN EXCELLENT EXAMPLE OF THE ENDURING QUALITY OF ROMAN CONCRETES USING VOLCANIC ASH.

CESAR MANRIQUE'S ARCHITECTURE SEAMLESSLY INTEGRATES THE VOLCANIC LANDSCAPE.

“Mount Etna is a mine without miners; it is excavating itself to expose its raw materials.”

-Formafantasma

When Formafantasma visited the region of Mount Etna they were fascinated by the changing landscape from day to day due to constant eruptions. They were compelled by the idea of nature acting like a miner, expelling minerals and valuable materials without human intervention.

Volcanic eruption during a visit to mount Etna.

effects of Etna's eruptions on surrounding landscapes.

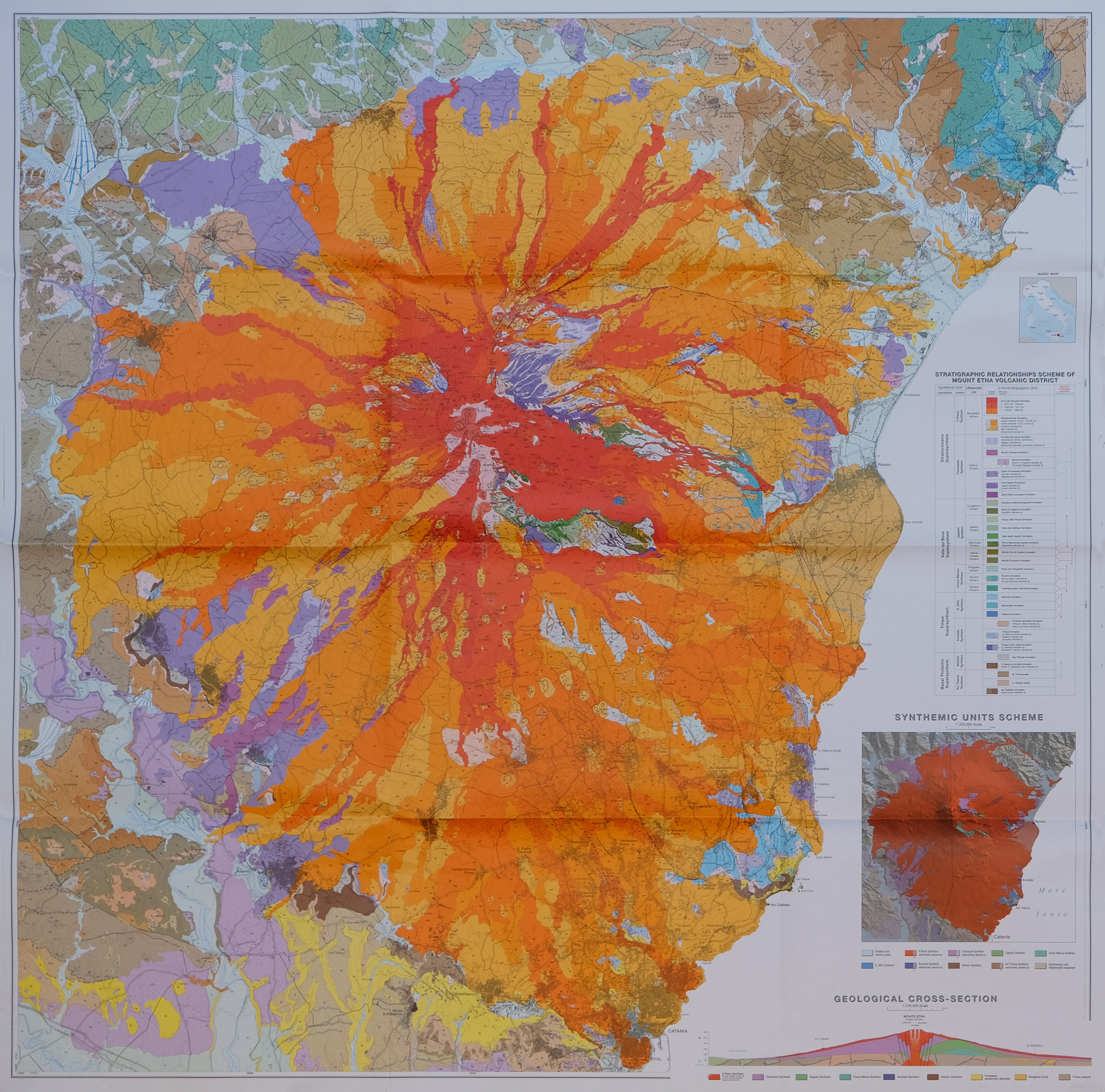

Detailed mapping of lava flows across different years.

Milan-based design studio Formafantasma have been researching the potential of volcanic lava as a design material since 2010. Andrea Trimarchi, one of the two founders of Formafantasma, grew up in Sicily against the dramatic backdrop of Mount Etna. Over time, Trimarchi and partner Simone Farresin have observed the detrimental impact of mass-tourism on both the landscape and culture of Sicily. Their 2014 project, De Natura Fossilium, addressed this by thoroughly investigating the culture of lava in the Mount Etna and Stromboli regions of Italy and culminating in a collection of expertly-crafted glass, basalt and textile works.

The ExCinere project was conceived as a means to further explore the application of this most fascinating naturally-occurring, self-generating, and abundant material. Dzek and Formafantasma have collaborated to produce a useful architectural product that makes full use of volcanic lava’s material properties.

volcanic rock.

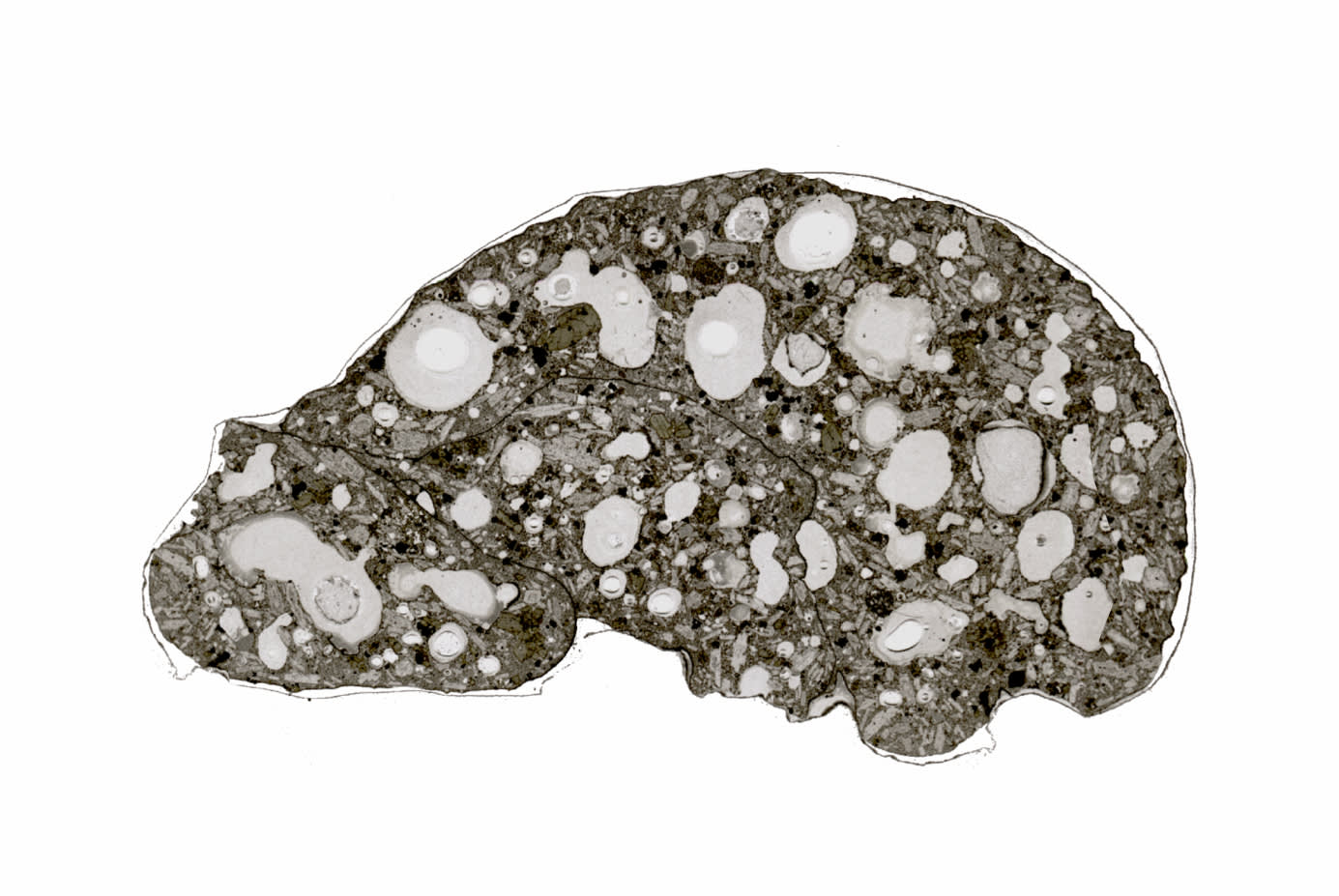

Microscopic imagery of volcanic matter.

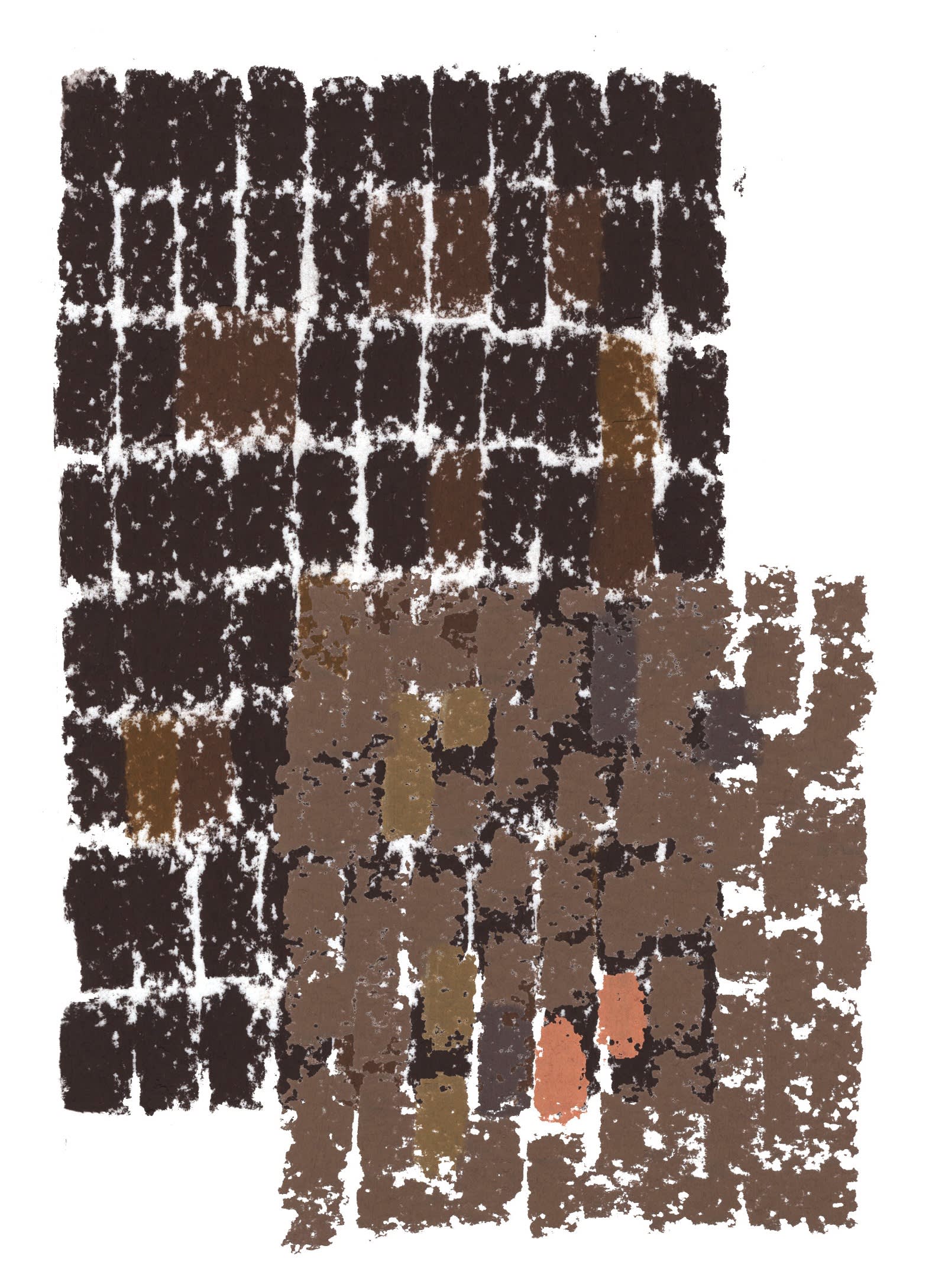

Early volcanic rock glaze trials by formafantasma.

Vessel and sculptural works from the De Natura Fossilium series.

The relationship between the human and the volcano; one of the most visceral symbols for the untameable force of nature, is ridden with allegory. And so this project also became a battle of wills between man and volcano. Although Volcanic ash and basalt rock may appear inert, their high metal oxide content makes them complex and unpredictable to work with. Three years of exploding, imploding, cracking and caving were endured before ExCinere’s careful balance of gres porcelain body, ash glazes, firing temperatures and method was achieved.

ExCinere glaze trials.

Concept sketch for ExCinere by Formafantasma.

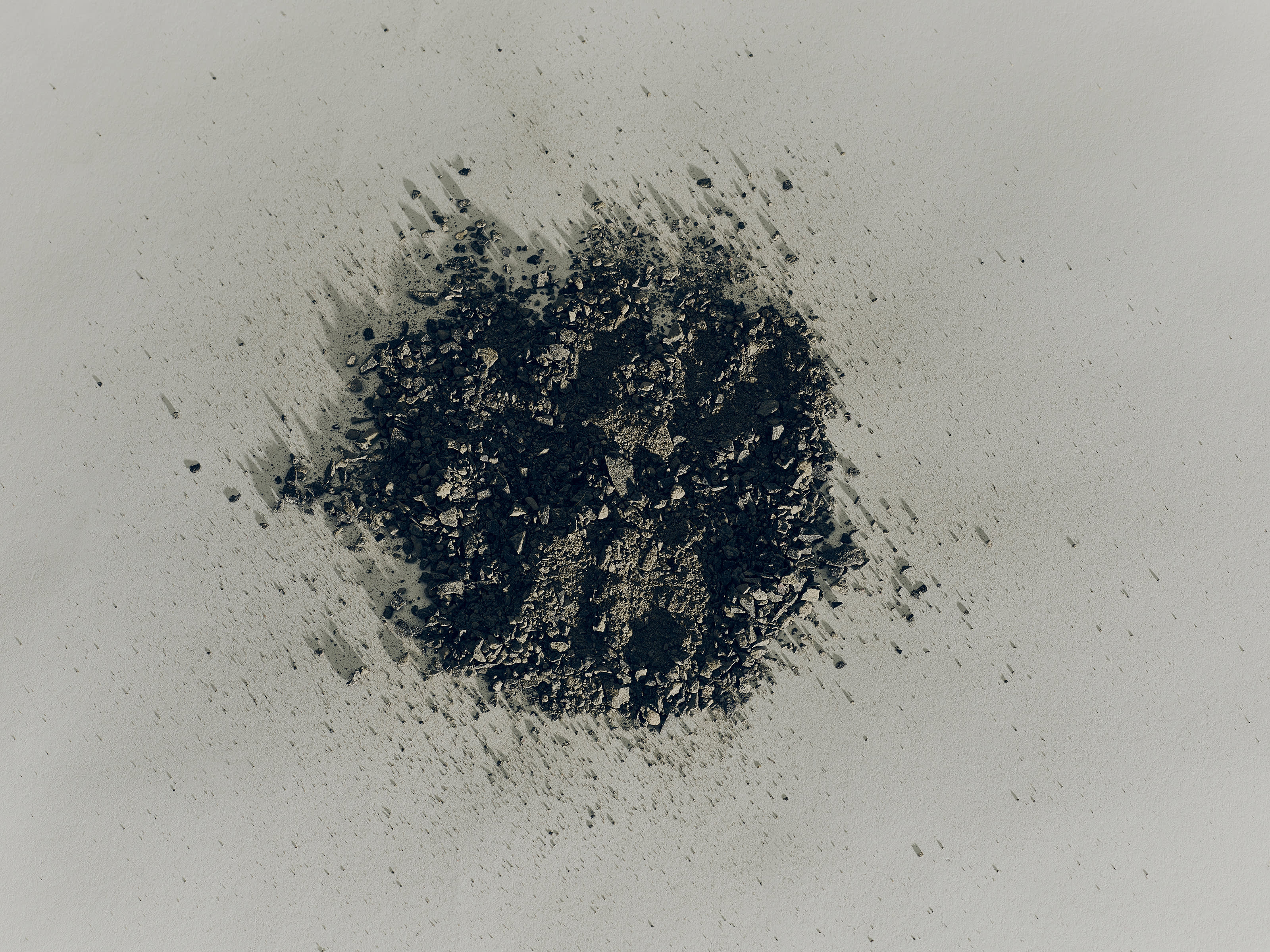

Mixed particles of volcanic ash.

PROCESS

Sieving the volcanic ash into different particles for glaze production.

Volcanic ash in different particle sizes.

Precise measurements to determine different glaze colours.

OUR LONG FORMAT BODY READY FOR GLAZING

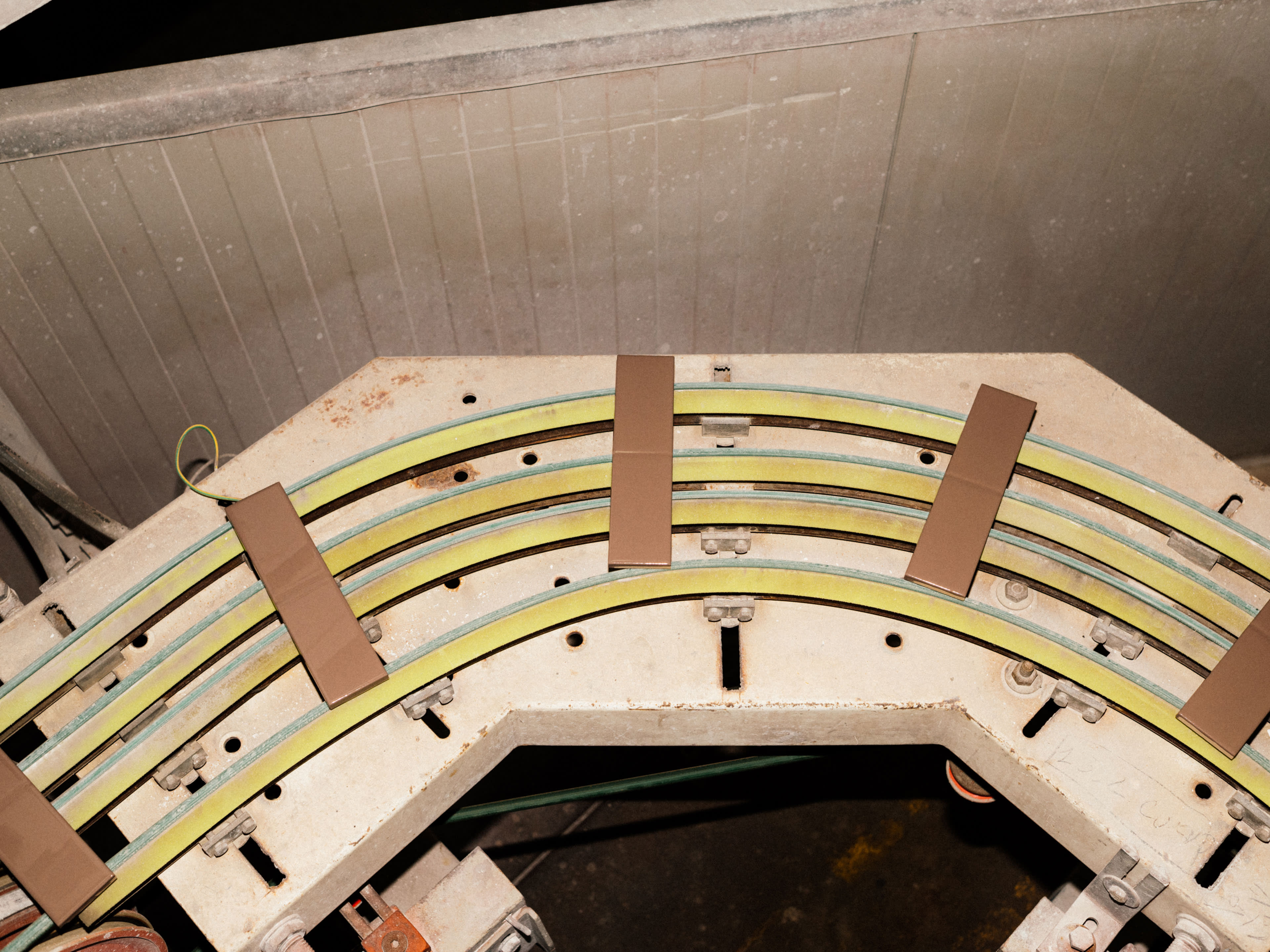

LOADING THE BISCUIT ONTO THE GLAZING LINE

WATERFALL GLAZING THE BISCUIT

GLAZED BISCUIT MOVES DOWN THE LINE

FIRING THE GLAZED TILES IN THE KILN

FULLY GLAZED EXCINERE TERRA TILES COMING OUT OF THE KILN

BOXING

ExCinere® is a refined collection of volcanic ash-glazed tiles suitable for both interior and exterior surfaces; from kitchen counters and bathroom floors to architectural facade cladding. The tile is available in two sizes and four volcanic glazes. These various surfaces are created by mixing varying quantities, particle sizes and densities of volcanic matter, resulting in surfaces that are evocative of the dynamic landscape from which they come.

ESSAY

Volcano and The Human

by Laura Houseley

Before we understood volcanic eruptions as manifestations of geothermal forces, humans believed in Typhon, the giant serpent of Greek mythology who slept peacefully beneath Mount Etna until rudely awoken, upon which he expressed his annoyance through explosions of fire and lava. Or Hephaestus, the productive god of fire tasked with forging thunderbolts for Jupiter and weapons for Mars, his commissions marked by the sparks flying from Vesuvius and Stromboli. Then there was Pele, the irritable goddess prone to fiery and deadly outbursts across the Hawaiian archipelago. But even as terrible and unknowable forces have dominated the communities who live beside volcanoes, those same populations have exploited the benefits of a volcanic landscape, putting to good use the extraordinary material expelled from exploding mountains in the form of molten lava, rock and ash.

Such opportunism is succinctly illustrated by the Bronze Age gardens of Pantelleria – beautifully simple agricultural structures built from jagged volcanic rocks, each one like a gloved fist gently enclosing a single fruit tree, its thick circular walls protecting the precious fruit from the wild winds that ravage the otherwise bleak and exposed landscape. This primitive volcanic architecture has proven effective; after three thousand years the buildings still stand, the fruit is preserved. The gardens of Pantelleria are among the earliest examples of volcanic material being used proactively – of humans building, literally, a paradox between the most mighty and destructive of natural forces and its latent benevolence.

It is this relationship between volcano and human, forever ricocheting between fear and awe, productivity and utility, that has gripped Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin of Formafantasma. Their work traces through time the cultural resonance of volcanic material and its applications, and has explored the ways in which volcanic rock and ash can be used today in object design and architecture. On the islands of the Azores you will find clusters of small buildings with walls built from a dense black rock that absorbs the bright sunlight. The stones have been fashioned into shapes we might politely call cubes, but are most definitely not uniformly so. Their outer faces are left unfinished and coarse, a vernacular trait that speaks clearly of this hard rock’s objection to tools. The stones are laid atop one another as in a characteristic dry-stone wall, the weight of the material itself and careful Tetris-like alignments making cement unnecessary. This is how basalt, the igneous rock formed from molten lava, rich in magnesium and iron and low in silica, has been traditionally and uniformly used by those living in the shadow of volcanoes across the globe. It is a rock that is easily accessible, sitting near to the earth’s surface. It is self-generating and exceptionally tough. See likewise the grass-roofed homesteads of Iceland, the villages of Cape Verde in Africa, the ancient construction of Nan Madol in the Federated States of Micronesia. Evolution of the vernacular use of lava stone in architecture was, in Sicily’s case at least, determined by Mount Etna itself, which erupted in 1669, causing huge destruction. The mass rebuilding that followed made elegant use of the same volcanic material that had caused the ruination in the first place. Catania emerged reimagined, with shining basalt paving and lively flourishes of ornate carved architectural work.

The somewhat paradox between reliance and intimidation felt by southern Sicilian communities was captured on celluloid by Roberto Rossellini in his 1950 film Stromboli. As Ingrid Bergman’s Karin rails against her inhospitable environs, the volcano becomes a metaphor for oppression, yet the documentary-style film also paints a portrait of a community in concert with their unruly home. The border between reality and art blurred to the extreme when Stromboli erupted during filming, providing Rossellini with footage of an actual evacuation. Today, the tension and concordance between such communities and their volcanoes has changed little: Stromboli erupted again in 2019, killing one person and covering the village of Ginostra in a carpet of ash. The devastating 2019 eruption at White Island in New Zealand was also a stark reminder of how deadly the natural landscape can be.

The relationship between lava rock and the landscape is especially intimate. As volcanoes erupt, the material they produce swiftly changes the shape and structure of the land, sculpting a new reality, leaving behind a new material makeup. As Formafantasma poetically put it, ‘Mount Etna is a mine without miners; it is excavating itself to expose its raw materials.’ Spanish architect César Manrique felt this relation between lava rock and landscape keenly. He designed and built a series of buildings across the island of Lanzarote, in the Canary Islands off the West African coast, during the 1960s that amounted to a bold new vernacular style for lava. Here the boundary between land and architecture is obscured; jagged rocks protrude through walls and windows into interiors as though the once dynamic lava field beyond were breaking through the architecture. In 1940s Mexico City, Luis Barragán devised a whole neighbourhood that would preserve and respect the characteristics of a lava field. The plan for Jardines del Pedregal included roads, plazas, walls and gardens that followed the contours of the lava flow. For Barragán, the untamed, uncolonised lava field represented Mexico itself and was the perfect location not just for a new architectural style but for the promotion of a new, learned Mexican middle class. His ideological vision included swaths of ‘garden’ that left lava rock exposed and raw between the midcentury villas. It was a shockingly alternative, and short-lived, approach. Today most of the lava field is concealed beneath pavement and parking lots, tamed and quelled.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Romans were the first to understand the full breadth of potential for volcanic material. Not only did they use the hard basalt in architecture, applying sophisticated construction innovations to fashion the rock into glistening columns and sculpture, but they harvested mineral-rich ash to use as fertiliser on grapevines and other crops. Recognising its inherent strength, they made basalt the material of choice for Roman roads. Even more impressive was the invention of Roman concrete. This was the curiously contemporary building material that facilitated architectural masterpieces like the Pantheon. Although the exact recipe has evaded historians, scientists and architects alike, we know that volcanic ash is the special ingredient that gives the material its unquestionable longevity. Roman concrete binds extensive fortifying sea defences. The mix of volcanic ash, lime (calcium oxide), seawater and lumps of volcanic rock holds together piers, breakwaters and harbours. Over time, the seawater that has seeped through the concrete has dissolved the volcanic crystals and glasses, with new minerals crystallising in their place, miraculously making the structures even stronger. In comparison, the concrete we use today (nineteen billion tons of Portland cement per annum) has a lifespan of mere decades and accounts for 7 percent of industrial carbon dioxide production.

Despite centuries of ingenious applications of volcanic material in architecture, design and agriculture, volcanology – the scientific study of volcanoes and volcanic phenomena – didn’t begin in earnest until the early eighteenth century, when the heady combination of uncharted scientific territory and intrepid adventuring required to investigate Europe’s volcanoes proved irresistible to the romantic Victorians. Artists, scientists and adventurers dashed to the Mediterranean to witness Stromboli and Vulcano in action. Understanding volcanoes in the eighteenth century meant understanding the formation of the Earth for the first time and rejecting biblical teachings, and was therefore hugely contentious – but fashionable nonetheless. Whilst chemists and scientists published their papers, others mined the commercial and creative possibilities of mineralogy and volcanology.

Josiah Wedgwood was one of the era’s most influential characters. He established the hugely popular Wedgwood ceramic factory, which became a blueprint for the modern commercial industry, and went on to influence the aesthetics of the day with his stylish interior objects. Wedgwood launched his Black Basalt pottery collection in 1768. This best-selling series of ceramic tableware and ornaments was modelled on ancient artefacts such as Egyptian scarabs and urns. Wedgwood’s interpretive ceramics used a matte black clay to mimic the volcanic basalt stone from which the originals were carved. He perfected a fine-grain stoneware, moulded into neoclassical styles with a dense uniform surface requiring no glaze, polished to a dull gloss. Wedgwood boasted that his stoneware would ‘last forever’, just like proper basalt.

Applying the iconography of volcanic matter as Wedgwood did (rather than working with the stuff itself) was the course taken by all but the most ardent craftspeople in modern times. Consider the Fat Lava vases of the 1970s, with their make-believe magma glazes. Or lava lamps even – molten matter as kitsch. Object designs using actual volcanic material remain a rarity due to the inescapable fact that its high mineral content and density make it a most difficult and unreliable material to manipulate. Those who have worked directly with lava are fabled. Consider the craftspeople of southern Italy who were known for capturing magma in its molten state from the very edge of a lava field and directly moulding it into objects right there on the mountainside. They used the volcano as not only mine and miner but foundry too. The process has all but died out completely and is now used only to fashion tourist souvenirs. Returning volcanic sand to a molten glass-like substance and moulding and blowing it; crushing, cutting and carving basalt rock; or working with ash and ceramic bodies are all processes Formafantasma has explored in their volcanic projects. Formafantasma’s studies of volcanic matter have been extensive. They have followed the path of crumbs left by centuries of craftspeople and pursued the clues of volcanologists and scientists in order to uncover the potential of volcanic material. The ExCinere volcanic ash-glazed tiles are a success, produced using a carefully balanced formula of particle size, density and firing temperature. This most exceptional material did not give up its secrets easily, but it makes for a fitting analogy that the process has been difficult. ExCinere is one of only a handful of commercial products made today from raw volcanic matter. It can be considered an important advance in the relation between volcano and human – another reflection on our fascination with this most violent and mesmerising of landscapes, and a confirmation of nature’s untameable pre-eminence.